An atheist single mom set out to shock the religious fanatics and ended up staying

Sibyl Sender (1934–2014)

17 minute read

Read MoreGrowing up in the predominantly white Bruderhof, Rubén was only vaguely aware that he was different. Then, in the second grade, his class made a field trip to a nearby public school, and a kid on the playground there called him the n-word. Today, a senior at City College in Harlem – one of the nation’s most diverse campuses in its best-known African-American neighborhood – he says he is still learning who he is. Far more importantly, his eyes are being opened to the realities of inequality and injustice, and he is learning through real-life experiences how the people most affected think these injustices can be overcome.

Rubén’s first teacher was his father, a tough-as-nails Puerto Rican who was raised on the streets of Brooklyn and went to prison at seventeen. After being released ten years later, he struggled with drugs and alcohol, and ended up at The Bowery Mission, a Christian organization that helps people escape homelessness and addiction. There he met a group of volunteers from the Bruderhof. After several years of off-and-on visiting, he joined. In 1993, he married Emilie, who had been raised within the community.

When Rubén was three, recurring battles with alcoholism led his father to leave the family and the community, and for the next several years, his mother raised him on her own. When he was ten, his father returned, and the family was reunited.

Only now, as an adult, does Rubén realize how much his father shaped his cultural identity in those critical years. A lot of it he simply absorbed:

He loved to cook, and in summer he’d invite anyone who wanted to join us in front of our house. He’d turn up his music – salsa, merengue, reggae, hip-hop – and then start preparing the food: arroz con gandules, arroz con pollo, octopus salad, and all kinds of things. Mom, who also likes to cook, would make dessert. Afterward we’d play stickball for hours, while my dad’s cat, Brooklyn, and my dog, Shea, would chase each other and fight and add to the general craziness.

But just as much was transmitted through intentional lessons:

Anyway, one day when I was in sixth grade he pulls down this book and says, “You need to read this.” It was Chancellor Williams’s The Destruction of Black Civilization, an Afrocentric history of the colonization of Africa. It’s openly biased, but important because it’s from a perspective you won’t find in any standard histories.

I told him, “I’m not reading that big fat thing.” But he was like, “Yeah, you are.” I did plow my way through it over time, and, more than any other book, it’s the one that got me interested in my major, history. It got me interested in digging for the truth.

Rubén’s father also opened his eyes to many social justice issues:

Take the Puerto Rican nationalists of the sixties and seventies. That was a cause Dad believed in, and he didn’t just show it by the flag that was always hanging in our living room. He was passionate about the history of oppression on the island. He told me about the mass sterilization of Puerto Rican women in the 1950s, and about the repression of the Young Lords, who started out as a street gang in Chicago but became known for their activism.

Another thing that concerned Dad was mass incarceration and capital punishment. As someone who had been incarcerated, he was set on raising awareness of what he called the “rotten-ass system.”

Love does not begin and end the way we seem to think it does. Love is a battle. Love is a war. Love is growing up.

The war and famine in Darfur was another major concern of his, and in 2008 our family traveled to the Sudan to see what was going on firsthand. We went with an organization our community had donated to, though Dad was just as interested in the history of the region, which is regarded as the birthplace of the Nubian kingdom. That trip opened my eyes to the reality of suffering in many ways, but there’s one particular incident I’ll never forget: in one village we stopped at, a woman tried to give my mother her baby. She literally begged Mom to take the baby back to America with us, and said, “He’s just going to die if he grows up here.” I can still see her face.

By 2010, Rubén’s father was struggling with his addictions again and decided to leave once more.

I was in the eighth grade, and struggling with who I was in this community where almost everybody else had two parents, and things seemed to be going fine. I was always popular at school and had good grades, but I was all beat up inside and would often get angry at home.

But even if his father wasn’t physically present, Rubén says the memory of his lessons continued to guide him:

I began to realize why my dad had exposed me to so many things and told me so many stories about his life. He had wanted to make me aware of things I would one day face on my own. In fact, he once said as much: “These are my experiences, and they made me who I am, but you’re different than me, so you’re going to have to fight your own battles and figure things out for yourself.”

During his father’s absence, Rubén says it was his mother who exerted the single most powerful influence on his developing view of the world:

Mom’s family is German-American, from the Midwest. Culturally, she had nothing in common with my father, but in terms of her concerns, she was the same. For example: she’d often drive me to neighbors and friends outside the community. We would have dinner with them and discuss things. One woman I especially remember worked with juvenile delinquents. Mom made sure I listened to this woman about her experiences with the courts.

In late 2012, Rubén’s father returned. He died at the Bruderhof several months later, of heart disease. Two years later Rubén graduated from high school. He spent a gap year in Australia before moving to New York City to go to college. He became a full member of the Bruderhof in April 2019.

Not surprisingly, living in Harlem has brought to life the stories his father used to tell him in a way he never could have imagined from the protected vantage point of his childhood:

I used to think, “Wow, Dad went through all this stuff? That’s crazy.” But now it doesn’t surprise me at all. The things that happened to him are not so far out. They happen all the time. Racism is still alive and well. It’s wrong. It’s maddening. It seems archaic. But the particulars aren’t illegal, so it goes on and on, and millions of people are trapped in it.

Asked for his insights on how injustice can be fought, Rubén says that one of the biggest obstacles to progress is people’s inability – or unwillingness – to admit that certain problems exist.

Take something like racism, or more specifically, police brutality and the way it affects people of color. To many whites, it’s just a made-up thing. They so badly wish it was over and done with that they only see what they want to see.

But hey, I live in Harlem, and I’ve witnessed it. I’ve seen a boy riding a bike, and five cops jumping on him and just slamming him to the ground. Or take a movement like Black Lives Matter. I’ve heard people dismiss it by saying, “All lives matter.” Of course every life matters, but that’s a cynical response. Or they say they get the basic issue, but not the anger behind it. They seem unable to see that there might be a cause for that anger, and that you can’t just condemn it and hope it will go away.

Unless you have had a personal experience connected with a life-and-death issue like this, maybe you shouldn’t make too many sweeping statements. And if you don’t have that connection, maybe you should take time to listen to someone who is actually affected by it.

I think justice can begin when people are no longer trapped by external circumstances or victimized by the power other people hold over them. For those of us who already have those freedoms, I think it’s a call to action: to respect the culture and history of whoever is disenfranchised. And to show solidarity in the sense of being willing to learn, rather than always wanting to be the teacher. And to make sacrifices so that others can have a chance at getting ahead.

People – I’m talking about all races here – tend to congregate with their own kind, with others who have similar backgrounds and life experiences. And so the cycle continues. It’s just a fact that if you can’t understand the people “on the other side,” the easiest solution is to ignore them. But the problem is that in the long run, you end up being scared of each other.

My dad’s feeling for justice came from a personal place. His anger and his energy came from what he experienced as a child and young man. And yet he ended up joining the Bruderhof. That used to puzzle me. Now I see that he deliberately chose to live in a way where he could break down the walls that separate people. I think joining the community was a deliberate move toward that. In fact, he told me multiple times, “Yeah, I believe that people should live together and work out their differences.” So even though he knew what racism was, he still wasn’t scared to live with white people or to marry a white woman. I honestly think that at least in part, it was to break down the barriers of inequality, first of all for himself, because he didn’t want to be trapped in a world of us versus them. He was looking for true justice, the kind built on love and community.

17 minute read

Read More2 minute read

Read More2 minute read

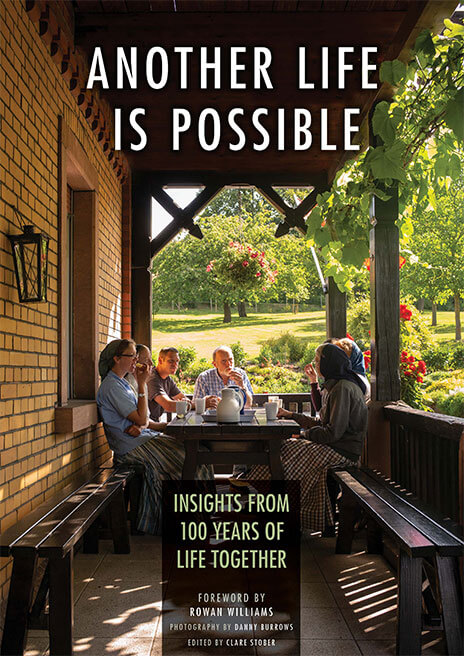

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.