She was determined to make a difference and transform the world

Erna Albertz (1979 –)

7 minute read

Read MoreIn 2014, Shannon graduated from the Bruderhof’s Mount Academy, left home, and spent a year at a Bruderhof in Australia before deciding to try her own wings. With the community’s help, she found an opening for volunteer staff at Casa Juan Diego, a Catholic Worker house in Houston.

Founded in 1980, Casa is the city’s best-known refuge for recent arrivals to the United States. Aside from the hundreds of immigrants that Casa weekly assists at the door, more than one hundred thousand have been given shelter in its overnight quarters over the years. No matter their origin, Casa welcomes them with hospitality, food, clothing, and medical care – all offered at no cost.

Working at Casa meant participating in daily dramas, most of them heartbreaking.

Pregnant women who had been raped by “coyotes” and were seeking abortions. Immigrant mothers looking for missing children. Criminals wanted by the police. A large man, high on drugs, who entered my office and, blocking the door, demanded food. A violent, mentally deranged woman whom I had to drive to a psych ward, where I spent an entire day convincing three professionals that they needed to intern the woman, that I could absolutely not take her back. And then there was a three-week period when, because of staffing issues, I was running the entire place alone. I was nineteen, and my Spanish was only borderline adequate, in terms of projecting authority. It was tough, very tough. But I survived, and after that nothing really scared me.

Run by volunteers and funded by donations, Casa doesn’t lack wealthy patrons.

The affluence in Houston is unreal. At Christmas truckloads of donations rolled in. A lot of it was trash, and so we’d have to sort it all. But even the useful stuff was overwhelming, in terms of the sheer volume. By the end of the holidays I was literally sick of dealing with material things. Meanwhile, what we really needed was people: to staff the clinic, drive trips, and respond to the constant requests at the door. Houston may be the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the country, but we at Casa often felt very alone, holding up hundreds of people for whom the city offered very few legal or financial safety nets.

And yet, no matter how much energy Shannon and her fellow volunteers expended on behalf of the people under their care, it seemed that the gulf between givers and takers, helpers and those in need of help could never be breached.

We were giving almost everything, but never the last inch: we could still get into our cars when we needed to and drive away from it all. Houston is ringed with gated communities, and I often spent time decompressing at the home of a friend who lived in one. I had that liberty; my guests did not. That dichotomy kept me thinking about how all this colossal amount of human effort, mine included, still fell short of justice, of countering inequality. We were still divided, haves and have-nots. I was still playing into the hands of an unjust system.

As she grappled with these questions, Shannon marveled at the dedication of Mark and Louise Zwick, the founders of Casa:

To them, what others might call social work was simply a calling – a way of quietly trying to fulfill Jesus’s demand to love one’s neighbors as oneself, regardless of trending hype and shifting politics. Mark was dying of Parkinson’s and I couldn’t see how Louise could continue their work in the long run. Personally, I knew that what I was doing was unsustainable, in terms of the resources in my own heart.

That Easter, Shannon visited Woodcrest over Holy Week and Easter. It was a decisive week. During the Good Friday service, she says: “I remember tears streaming down my face and thinking: Jesus’ hand is the only one that is big enough for all of this. And also big enough for me.” She completed her year at Casa and then returned to the Bruderhof.

We were giving almost everything, but never the last inch: we could still get into our cars when we needed to and drive away from it all.

Shannon is currently pursuing a literature degree in Bogotá, Colombia, with the hopes of directing her skills and energies into the Plough Publishing House after graduating. Still, her experiences in Houston go with her:

As one who has walked in its broken spaces, I can’t be okay with our fractured society. I feel responsible for what I’ve seen, for those realities and individuals which most people who are “making it” would rather not think about. We prefer to build walls – concrete and virtual – to keep it all distant, to keep us all apart. I now believe that the first and most important step toward changing this is to try to truly understand the “other side.” In reality, that means the other person. Reducing individuals to a group or entity, reducing them to an “other” status, is easy. It relieves us of the imperative to love them as we love ourselves.

But if I really believe that each of us on this planet is equally human, then I can never belittle or dismiss someone, or cast them in a stupid or inferior light. I’m not advocating some artificial equilibrium in which we all neatly sidestep each other, and no one speaks the truth. Still, in our fight for justice, one fact is crucial: there is no other side. There’s just other people, and this truth affords us both the liberty and the responsibility to respond to them.

7 minute read

Read More7 minute read

Read More3 minute read

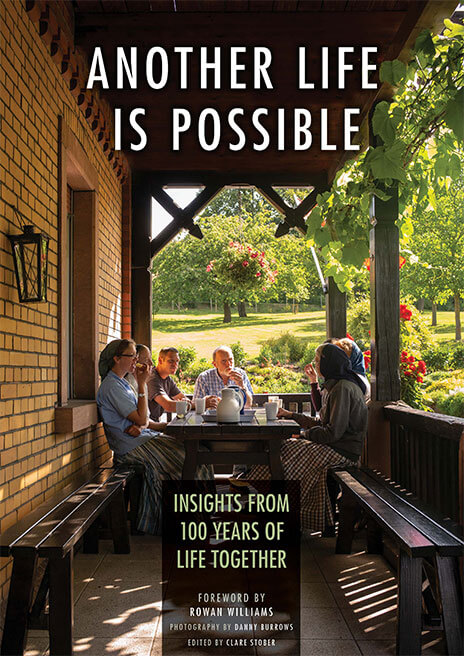

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.