A successful entrepreneur who realized that living a life of meaning had nothing to do with wealth

Clare Stober (1955 –)

8 minute read

Read MoreRaised in New York, Texas, and Florida, Sibyl was the only child of upper-middle-class parents. After attending an exclusive school for girls, she enrolled at Radcliffe, the then all-male Harvard’s separate college for women. Her wedding was announced in the New York Times. She was listed in the Social Register, the Northeast’s go-to index of patrician families and members of high society. But in spite of all that, she defied the “stultifying conventions” of her upbringing, most especially the patina of religion provided by her family’s occasional churchgoing, which she denounced as an “utter farce.”

My story is a typical atheist’s story. We come into the world with a preconceived idea. It’s as if we have a pre-birth memory of better days. By the time of my fourth birthday, I knew the place was a mess. Burdened by an image of children lying, fly-covered, in gutters in India, I was sure I could do a better job, and vaguely wished, as I blew out the ritual candles on the cake, that whoever was in control would “make it all better.”

Of course nothing got better. If anything, it got worse. At four and a half I attended my first Sunday school class. Upon being told where we were going, I thought, “At last, a chance to meet God face to face.” Instead, we cut out white sheep and pasted them on green paper. Institutional religion never recouped itself in my eyes.

By the time I was fourteen, I had come to the end of my tether, inwardly. There was an overabundance of badness and, worst of all, I was beginning to see that the goodness was about 95 percent phony. In California, a three-year-old child lay dying in a narrow drainpipe she had fallen into. As men and machines tried to extract her, the entire nation prayed for her safe release. It was time for a showdown. “This is it, God, your last chance,” I thought. “Get her out alive, or we’re finished. Look, if it were left to me, I’d save her without even being worshiped.” She died in the pipe.

Though I smoked hard, and drank hard, and lived hard, I could not suppress a wrenching, clawing feeling that there might be a meaning to life, after all.

So it was all over. The child and my regard for God were equally dead. Now I knew that human beings were nothing but animated blobs of protoplasm.

Then there was the idiocy of morality. It appeared to be deeply rooted in “what the neighbors would think.” And what the neighbors thought depended on where you lived. Morals, ethics, right and wrong, they were all purely cultural phenomena. Everyone was playing the game. I opted for nihilism and sensuality. And lived accordingly. Out with good and evil, out with morality of any kind, out with accepted cultural customs.

A line from Knock on Any Door, a 1949 film, summed it up: “Live fast, die young, and leave a good-looking corpse.” I proceeded to live my beliefs, preaching atheism to any idiot who “believed.” Though I smoked hard, and drank hard, and lived hard, I could not suppress a wrenching, clawing feeling that there might be a meaning to life, after all. In retrospect I see that I was so hungry, so aching for God that I was trying to taunt him out of the clouds.

During high school, my two closest friends and I discussed philosophy endlessly, worked on the God question, reaffirmed our atheism, and read C. S. Lewis so that, in case we’d really meet him one day, we’d be ready to “cut him down.” Attendance at chapel was required, but I refused, as a matter of conscience, to bow my head during prayers. Caught, I was banished to the back row, where I defiantly sat and read Freud.

Radcliffe, she soon discovered, “was as phony as church,” so she dropped out and married Ramón, a student at Brandeis and the son of a dissident Spanish novelist whose mother had been executed by the forces of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco.

It was not long after this that a baby girl, Xaverie, was born to us. As I looked across the maternity ward of the big Brooklyn hospital where she was born, the absolute innocence and trust she radiated just tore at my heart. I could not understand how something so beautiful could be put into such a horrible, evil, cruel world. I knew I was a part of this world. I could not find the answer.

While I nursed her at night, I steeped myself in the writings of Dostoyevsky. Truths were coming at me, though I couldn’t have defined them then. Ramón and I had acquainted ourselves with various offbeat religions, but none held the slightest appeal for me. It was Dostoyevsky that was the real religious experience. Today I can say that he was the one who delineated, for me, the realization that humans are buffeted and driven by dark forces greater than themselves, and that these forces chain us all – and (as he suggested in the gentlest possible way) that another, stronger, freeing power exists.

By the time Sibyl’s daughter turned one, her marriage was falling apart, and Ramón had left the house. “I knew we bore equal blame,” she later recalled. “If I were him, I would have left me.”

My mode of life descended steadily into the swineherd’s berth. Sometime during what I considered a final separation from Ramón, the man I was currently “in love with” decided I should abort our child. I hoped to the last minute that he would change his mind. But he didn’t. And so, tough atheist that I was, I went through with the most devastating and most regretted ordeal of my life. Why, when I had been dedicated to the proposition that there was no such thing as right and wrong, when no intellectual, believer, or educator had been able to persuade me otherwise – why was I burdened with such guilt?

There soon came a time when Xaverie was all that stood between suicide and me. I had reached as close to the bottom as a person could. Then, on a hot August night in 1957, in surroundings I will not describe, I groaned to a Being I did not believe in, “Okay, if there’s another way, show me.” Two months later I was at the Bruderhof.

It all began with Ramón’s startling appearance in my Manhattan office. A year earlier, he had left New York to join the Beats in San Francisco – Kerouac, Ginsberg, and company – and we’d not seen each other since. Meanwhile, I was settled and had a good job as a magazine editor.

At a recent party in Greenwich Village, he had met someone who was on his way upstate to check out a religious community. Ramón had tagged along, and now he was on a mission to get me to visit this community.

Everything in me recoiled from the idea. The Christians I knew wore disapproving grimaces. They worried about their reputations. They were stiff and self-conscious – they waited for you to notice how good they were. Then, there was Ramón himself. I wanted nothing more to do with him. So I told him, “No, I’m not going anywhere with you, and most definitely not to some stupid religious joint.”

The Christians I knew wore disapproving grimaces. They worried about their reputations. They were stiff and self-conscious – they waited for you to notice how good they were.

Ramón left, but only to reappear a few weeks later. The same scene. It happened I don’t know how many times. Once he took me to a restaurant and wept. It wore me down. “Okay,” I finally told him. “I’ll come, next weekend. I’ll hate the Bruderhof and they’ll hate me. And then you’ll stop nagging me about it.”

I picked my traveling clothes carefully: my fire-engine-red knit tube dress. That ought to ensure immediate rejection. Friday afternoon Ramón drove Xaverie and me upstate. All the way, I was cultivating a venomous attitude toward “that place.”

Once she arrived at the community, however, none of Sibyl’s preconceived notions fit the realities that met her. In her own words, “Everything seemed to be turned inside out, and set on its head.” People greeted her, she later remembered, as if she were an old friend. So while Xaverie happily lost herself on a swing set, Sibyl, disarmed by a wave of love, found herself trapped in a life-changing dilemma.

And yet, I wasn’t going to leap into the burning bush, not me. There was always hope that the Bruderhof would reveal itself to be utterly phony.

The heavens and hells I lived through in the next forty-eight hours were as several entire lifetimes. How could I be moved to tears in half my being, while the other half scorned my reaction and told me I was surrounded by seemingly mindless adults trapped in spiritual schizophrenia?

On Sunday morning, I looked forward to surcease in the battle. Surely the “religious service” would cure me of these strange leanings toward “goodness” that I was feeling. It would be like every other nonsensical religious powwow I’d been to. Empty. Nothing there.

But then the service began, and horrors – they were reading Dostoyevsky! “God, don’t do this to me,” I found myself pleading. “Don’t hit me in the literary solar plexus like this!” It was a passage from The Brothers Karamazov, where Ivan, the intellectual, tells Alyosha, the believer, that he, Ivan, refuses to believe in a God who would countenance the torment of even one innocent child. There followed for me the spiritual denouement. Worlds, galaxies collided, and I quietly accepted and embraced a brand new thought: it is not God who torments the innocent. It is Sibyl.

Afterward, Sibyl found herself pouring out the entire wretched contents of her personal life to a complete stranger named Heinrich, a pastor at Woodcrest.

Later it seemed to me that in talking, the two of us had lived through the entire gospel, and that the heart of it was, as I had always suspected way deep down inside, “C’mon in, sit down, and have a cup of coffee.” It had nothing to do with wooden pews. It had to do with goodness’s compassionate love for badness.

At the end, I told Heinrich that this did not mean I was about to join the Bruderhof; I had to return to New York City. He said, “That is death.” I said, “I know.” Still, I was determined to get back home and pick up living again as if nothing had happened. So I did.

I spent the next three months trying to escape God and the call I felt – the call of total commitment, the death of the “old man.” Oh, how the devil tried to lure me – and how I tried to follow him! He offered me money and fame in the strangest ways. But I could not eat the foul dish he set before me. I turned from it in disgust. What had happened to me? My taste buds had changed; my eyes were different, my ears, my nose, my sense of touch. I was Sibyl poured into a differently perceiving vessel. In the end, I had nowhere to go but back to the Bruderhof, until I could decide which way I would go forever.

After returning a second time, Sibyl knew it was for good:

I was as one in love. I was utterly consumed by the life of the community. The struggles of each member – their joys and sorrows, openly shared – seemed to be mine. But it was more like an ongoing adventure in discovering God’s will. And it was punctuated by laughter, of all things! This adventure had nothing in common with a gloomy, introspective mining operation. Life was unutterably beautiful, wonderful. All I had been through – and was going through now, each day in community – was a miracle: of forgiveness, of mercy, of prayer, of God. And that a wretch like me was allowed this!

There was a price to be paid. Sibyl’s relationship with Ramón, which had never been stable or monogamous on either side, continued to crumble. In the end he left her once more, eventually divorcing her and moving to California. Sibyl was now a single mother raising Xaverie on her own.

Years later, when Xaverie decided to join the Bruderhof, Sibyl asked her: “How did you know what this was all about? I never used religious words.” She answered, “Oh, Mama, Jesus was everywhere.” This confirmed something Sibyl had always felt, that “if our deeds don’t bespeak God’s will, then there’s no point talking about him.”

In her late sixties, before moving to Bellvale, where she spent her last years, she told the Woodcrest community:

It’s no good if we live by traditions, or what other people think of us. It’ll be the death of our life together. In love there is total freedom. If we love our brothers and sisters, we can be totally free. If we don’t love them, we are going to become uptight, watching for rules and doing what you think people want you to do. Don’t let that happen or else I’m going to come back and raise HELL.

8 minute read

Read More11 minute read

Read More2 minute read

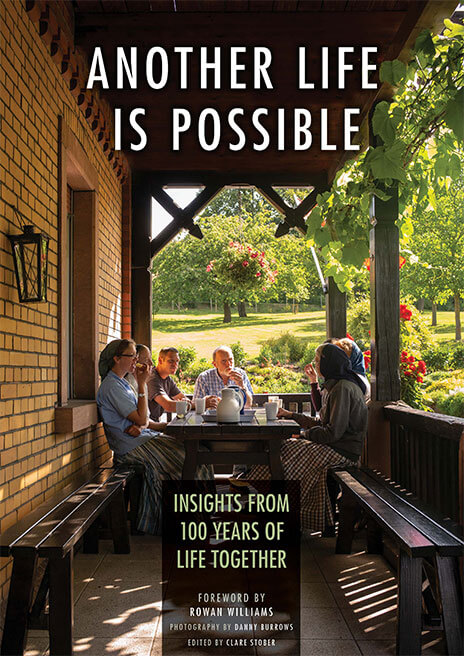

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.