Advice from a single mom dying of cancer

Adima Shirky (1994 –)

3 minute read

Read MoreBorn in Connecticut to British members of the Bruderhof, Dorothy, a nurse, has lived and worked in Nigeria, Australia, England, New York, and Germany, where she currently lives at the Holzland Bruderhof while working in the burns unit of a rehabilitation center. But no matter where she goes, there’s always one constant: her wish to help others.

Already as a child, I knew I wanted to help people. When a classmate had a mishap, and when my teacher had an ice-skating accident, I was interested in their injuries. I read The Day of the Bomb, which is about the aftermath of Hiroshima. I got involved in my school’s fundraising project for Vietnamese “boat people” – that was the refugee crisis of the late 1970s.

By the time I was fourteen, my family left the Bruderhof and I had lost my childhood faith. How could there be a good God, yet so much pain? I volunteered at a camp for teens with disabilities, and immersed myself in human rights issues while participating in Model UN and Model Congress.

When my parents returned to the Bruderhof, I decided to move out on my own. The Bruderhof was nice, I felt, but too comfortable. I wanted to do something about the needs of the world.

Late one night I climbed out onto the rooftop fire escape to look at the stars. There they were, in their familiar patterns, vast, silent, eternal. Suddenly I was aware of something powerful and good embracing the entire arch of heaven, as well as the whole earth. Since that moment, I have known that God is there, and good, and that all that is wrong stems from a separate and evil power waging invisible battle here on earth. And I was free to choose which power to serve!

First I moved to a small town near Jackson, Mississippi, and worked in an educational program there. From there I moved to St. Louis, where I worked at a treatment center for neglected and abused children. Soon I was answering ambulance calls for the city as an EMT and training to become a paramedic.

During this time, Dorothy began to see that the individual tragedies that surrounded her were the consequences of larger societal problems, and found herself grappling, once again, with the meaning of human suffering:

It often felt like we were trying to solve society’s problems with bandages: wiping the pus off the surface of the wounds and then covering them with clean dressings. Could anything stop the spread of the underlying cancer? I wondered about “my” kids at the center. In ten years, how many of those precious five-year-olds would be in jail or themselves young, overwhelmed moms, caught in cycles of neglect, abuse, and despair?

I discovered that being poor or oppressed is not a virtue; that is, it does not free people from selfishness, or from attempting to get ahead by pushing down others.

I felt bankrupt, and realized with a jolt that I was part of the problem. I was fueling these destructive forces with my own selfishness, my dishonesty, with my drive to be in control, to be right. I saw that it wasn’t enough to “serve people” as a neutral party. I had to allow light to totally cleanse and change my heart. At the same instant I knew that that light was Jesus, who had given sight to the blind, compassion to prostitutes, life to the dead. He had also said “love one another” and “become one.” I felt personally invited to the service of unity and love, of Jesus’ kingdom.

Not worrying over details, but knowing that she needed a community where she could be “part of a body” rather than an isolated pair of helping hands, Dorothy picked up the phone, dialed the nearest Bruderhof community a thousand miles away, and asked to come back and become a member. This moment of saying yes remains an anchor to her life of service in community, which has not been without struggle.

I felt bankrupt, and realized with a jolt that I was part of the problem. I was fueling these destructive forces with my own selfishness, my dishonesty, with my drive to be in control, to be right.

I remember panicking on my first day when I looked around the community dining room and saw all those healthy, happy, stable families. I momentarily felt I had forsaken “my” children in St. Louis. But then I imagined where everyone might be, if not for the gift of this church: some would be wealthy, some would be the victims of broken marriages, some would be at risk of neglect and abuse. It made me all the more determined to help build up a new, different society, on the basis of justice and love.

As it happened, the Bruderhof needed nurses at the time, and Dorothy was asked if she would be willing to go back to school.

After graduating, I worked in a little clinic run by our community alongside a doctor with decades of experience. Among other things, I learned the importance of humility, the readiness to admit when you’ve made a mistake. And I learned the value of working as a team, also with your patients’ families, instead of adhering to the professional hierarchies that separate people in so many healthcare settings. I learned more during my first year there than I’d learned all the way through nursing school.

As a member of the Bruderhof, Dorothy has had many opportunities to use her skills outside of the community. For example, she lived in New York City for several years, working as a hospice nurse case manager, making house calls to patients up and down Manhattan. She loved that work, often feeling that she was at the receiving end of these interactions with her patients. It wasn’t all easy, but offered important lessons.

My job included visiting patients in some of the most notorious housing projects in upper Manhattan. I often wore a stethoscope around my neck as a badge of intent. Once I found myself in an elevator where the only other passengers were young men whose black and gold marked them as Latin Kings. As I got off a few floors later, I said, as I always did, “Have a good day,” which was met by a vigorous volley of well-wishes: “Take care, ma’am!” “Get home safe!” Just kids, wanting to belong. I felt as secure as if they had been angels!

Late one afternoon in Harlem I saw a crowd gathering around an ambulance, and several squad cars, so I crossed the avenue and kept walking. Medics and police were trying to restrain a young man and load him into the rig. As the doors slammed shut, an elderly woman stepped forward, raised her arms and called out over the crowd, “Who is this man’s family? Who here is gonna pray for him?”

Being single was not my choice, but that’s how it worked out, and it had given me the chance to be available for service in a different way than if I had had a husband (with his work to take into consideration) or children to look after.

I immediately felt put to shame for only thinking about my own safety, and still hear this grandmother’s plea whenever I run into distressing situations – a highway accident, or a patient’s frustration. Whether or not I can help as a medical professional, there is always something else I can and need to do: pray that God intervenes.

After three decades on the job, Dorothy finds herself occupied with an issue familiar to anyone who works in the caring professions: the cost of possessing skills that are always useful, and always needed by someone.

I felt happy and fulfilled caring for children at a Bruderhof house in Germany, having finally learned enough German to interact with our neighbors. Just then, however, our communities in England put out a request for another nurse and I was asked, at a moment’s notice, to move there. For whatever reason, I found it very difficult. It wasn’t that it was a surprise. All members in our community promise to live and work wherever they are needed; and as a single woman and as a nurse, I’d moved many times, and was actually used to it.

Being single was not my choice, but that’s how it worked out, and it had given me the chance to be available for service in a different way than if I had had a husband (with his work to take into consideration) or children to look after. It has brought me the chance to travel again and again, and the freedom to respond wherever there was a need, whether for the short or long term. Sure, it often meant parting with friends and familiar routines, but I’d always seen it as a positive thing: an opportunity for a new beginning. This time, however, I suddenly realized that I wasn’t responding with the sense of adventure that I’d had in earlier years.

I thought: “You’re in your mid-fifties, and you still don’t really have a place you think of as home.” A friend tried to encourage me: “On the other hand, you have many homes – more than a dozen!” I moved, but struggled for months. Nevertheless, I was happy while working during this time, maybe because my vulnerability made me better able to hear the pain of others.

Then I remembered a book someone had given me years ago, when I was living in St. Louis, before I’d joined the Bruderhof. It was a used book from a thrift store, by Jean Vanier. It was called Community and Growth. In this book, there’s a wonderful chapter on gifts, and in it Vanier says that availability for service is one of the most marvelous gifts there is in a community.

When you hear that someone is gifted, you tend to think that they’re artistic or musical or very intelligent. And here is Vanier saying that availability is a great gift that we can each give one another. So I reread this, and found inspiration again.

I don’t know what opportunity might come up next, but I know that wherever I land, the chance for service will be there. The challenge is to not miss the opportunities that come along – to keep your heart open.

3 minute read

Read More2 minute read

Read More17 minute read

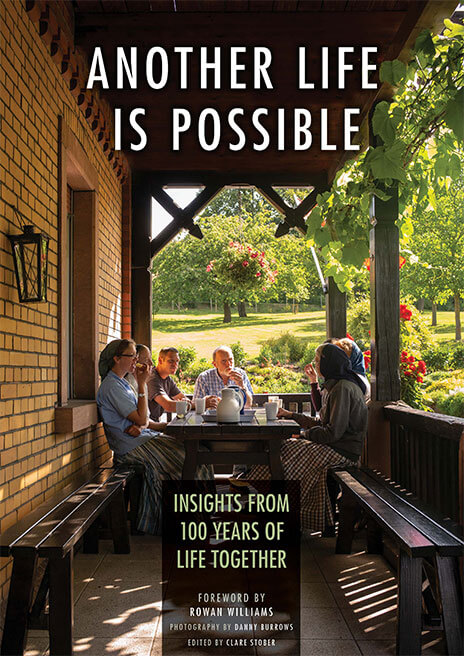

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.