A soldier in Saddam Hussein’s army who became convinced that he could no longer kill

Jacoub Sheghram (1958 –)

11 minute read

Read MoreJosef was born in Germany in 1929. One of his earliest memories was of a group of Nazi storm troopers marching through his street in the old merchant city of Frankfurt, singing, “When Jewish blood spurts from our knives . . .” A four-year-old, he did not know whose blood they were referring to, but the look on his parents’ faces was answer enough.

Not long afterward, the family left Germany for the apparent safety of Poland, where, a few years later, Hitler’s armies caught up with them. Driven from their homes on foot by the SS, they fled further east, to Russia, where they were interned with other Jews and then tricked into boarding a train of box cars headed for the freezing wilds of Siberia and its labor camps. Ironically, this probably saved Josef’s life: had his family been returned to Poland – their goal – they might have ended up in Auschwitz.

In 1943, after his mother’s death from starvation, Josef’s father sent Josef and his younger sister to an “absorption center” for displaced children near Haifa. By the end of the war, Josef was attending an agricultural school at a Zionist settlement. Among his peers were survivors of places such as Bergen-Belsen who, though teens like him, looked like old men.

Meanwhile, he remained a refugee in every sense of the word. When asked to name his mother tongue, he could give no clear answer. Most burdensome, his heart brimmed with hatred – for the Germans, because of the Holocaust, but even more for the English, because of their attempts to restrict the immigration of concentration camp survivors and refugees like him into the Promised Land.

Like other Jews, I promised myself that I would never again go like a sheep to slaughter, at least not without putting up a good fight. We felt we were living in a world of wild beasts, and we couldn’t see how we would survive unless we became like them.

The next years brought a stint in the Haganah, the underground military force then fighting for the establishment of the State of Israel. During one campaign, Josef served in a unit that forcibly evacuated Arab villagers from an area desired by Jewish settlers. He participated in interrogations, beatings, and even murder. This incident reopened the memory of his own suffering, which ate at him and brought on waves of guilt. He eventually left the army, then abandoned Judaism, and then religion as a whole:

Around this time I thought it was nonsense to believe in a higher power. After everything I had experienced and heard, I was indignant that my forefathers brought so much suffering on themselves through their faith in a god.

Over the next years Josef stopped looking for the purpose of human existence, and for a just, equitable society. Capitalism was abhorrent to him; Zionism, too, had lost its appeal. Socialism and communism held his interest for a while, as did the writings of Jean-Paul Sartre. He delved into Esperanto, an artificial language championed by postwar European intellectuals who believed that a universal tongue would bring about universal peace. For several months he tried living with a community of idealistic Marxists in Paris. He spent several months in Munich, where he was horrified to stumble upon a neo-Nazi march and find admiration for the Führer alive and well. The riddle of why human beings cannot live together in peace and harmony drove him to despair. On more than one occasion, suicide beckoned.

But from that point on, I have had no doubt. I found what I had been seeking. This is the only answer to humankind’s need, to open themselves to the spirit of God who wants to gather a people to live out his will.

In 1958 Josef came across the Bruderhof. There, in a Christian community, of all places, he felt confronted by the God of his ancestors as never before. Though a convinced atheist when he arrived, and a skeptic bent on disproving the viability of community, he was irrevocably drawn. As he recounts in his memoir, My Search:

Until that moment, my inexorable logic had excluded any such spiritual dimension. But from that point on, I have had no doubt. I found what I had been seeking. This is the only answer to humankind’s need, to open themselves to the spirit of God who wants to gather a people to live out his will.

I love the game of chess. In chess, it often takes a long time before you make a move. You look at all the possibilities and then you decide on your move. It looks completely logical since everything is all thought through. But sometimes your opponent makes a move that you hadn’t thought of at all; it goes against your whole logic. You realize that your whole approach was built on a false premise. You have to start from scratch, as if it were a completely new game.

Two years later, Josef committed his life to Christ through believer’s baptism.

Decades later, Josef was contacted by a man whose father had been driven out of the village Josef’s unit had forcibly evacuated when he was a soldier. This man had heard of Josef and was interested in meeting him. In 1997, with some trepidation, but also with fervent hopes of reconciliation, Josef traveled to Israel, where he met the man and his father, begged their forgiveness – and received it.

That trip encapsulates the way his quest for peace and his desire to be a peacemaker drove him onward, never resting or allowing that he had “arrived.” At his side, or waiting for him at home, was always Ruth, his beloved wife of fifty years. Together they had seven children.

In a broader sense, Josef was a father to many more than his own children, both within the Bruderhof and beyond it. His cheerful, sage advice and his self-effacing humility (he was famous for prefacing opinions with, “Forgive me if I am wrong . . .”) made him a trusted mentor to friends and acquaintances around the world.

When a massive heart attack took eighty-three-year-old Josef Ben-Eliezer, his family and hundreds of friends around the world were left stunned by the suddenness of his death. For Josef himself, it was a mercifully swift passage into the arms of a God he had once denied.

11 minute read

Read More17 minute read

Read More2 minute read

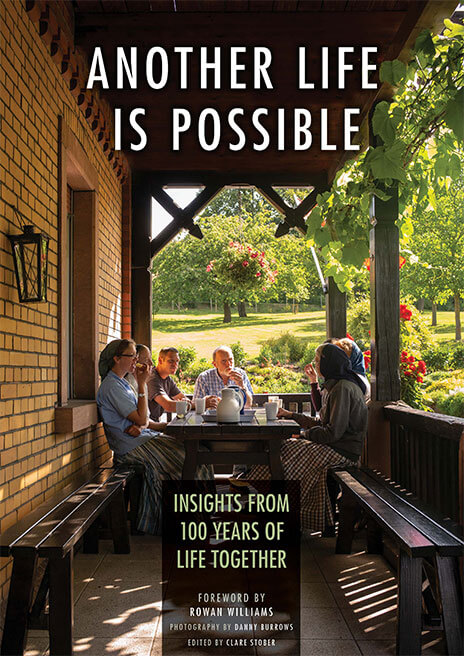

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.