Seminarian leaves the power struggles of academia for a life of service in community

Charles Moore (1956 –)

2 minute read

Read MoreKim’s journey from loneliness to community began during his childhood in Alabama:

I grew up in a single-parent household: just me and my mother. Naturally, as I grew up, I wondered where my father was. She told me he was a very important person who had important things to do – things that kept him away from our home – and that our job was to keep the home fires burning and make him proud. Not surprisingly, I created, over time, a sort of fantasy picture of the world’s greatest dad.

When Kim turned six his mother sent him to boarding school, a military academy that she hoped would instill discipline and perseverance in her son.

During his senior year of high school, Kim’s fantasies regarding his heritage were shattered. A half-brother he had never heard of showed up one day and took him to visit their father, who was dying:

We talked as we drove to the hospital, and the more my half-brother told me, the more it became apparent to me that my father was no hero but just a regular married man with a family who had, somewhere along the way, gotten involved with my mom; and that I was an accidental result of that relationship. When we got to the hospital I was not really prepared to meet him. The man I saw in that hospital bed was in no way the dad that I wanted. I left that room rejecting him, and in the process rejecting a big part of myself.

After high school, Kim attended Georgia Tech, where he studied engineering on a scholarship. But try as he might, he couldn’t shake the feelings of confusion and bitterness and even hatred that followed his brief encounter with his father. When an opportunity to stay in Europe opened up, he took it. It was a chance to get as far away as possible from the mess he was in.

Kim’s time in Hamburg was the happiest chapter of his life thus far: he was embraced by Ulrike’s extended family, which included not only her relatives but also the members of a vibrant network of youth groups associated with her church. He recalls:

These young people were grappling with finding a real faith: one that could be expressed and lived out, personally, and in society at large. They accepted me and made me feel that I was one of them.

And yet, the Comers grew uneasy with the pressures they faced as young professionals. In Kim’s words:

I never saw my training as my calling in life; I knew very well that it was a fluke. On the one hand, there was the supposed privilege of working at a university. In Germany, a sense of awe and wonder pervaded the air around people with academic titles. But it was so empty: all this prestige, though they hadn’t worked any harder than anyone else.

I was just coming into the final phase of my studies, finishing research and taking exams; and Ulrike was coming into the internship and residency phase of medical school. And both of us kept hearing these questions in the back of our minds: “What are we going to do with our lives, once we are finished with school? What is our vocation, our real calling?”

I kept on studying. Even though I sensed that my work wasn’t all that important, it was interesting. And once our son Clemens was born, I had to provide for him. Plus, my job had been created for me by the university and couldn’t have fit me better. My field of research was the transmission of ancient Greek mathematics through the Middle Ages, and I knew of only one other person specializing in it at the time – some guy in Austin. So I threw myself into producing quality academic work, getting published, speaking at conferences.

Despite our best intentions, we were increasingly caught up in the rat race and the need to present ourselves as “successful.” Our lives were so disjointed.

During the first year or two of our relationship, we were involved with youth work and the Salvation Army; we attended Bible study. By the time our second child, Bennet, came along, such activities were falling by the wayside, and we were being supported by our church, rather than the other way around: for example, an older lady came to take our kids out for walks when we felt that we should actually be supporting her. Despite our best intentions, we were increasingly caught up in the rat race and the need to present ourselves as “successful.” Our lives were so disjointed.

Then two events brought everything to a head. The first happened on the night of January 17, 1991, when the United States began bombing Baghdad. I was at the university, working late on some important papers that were to be presented at some important conference on some very unimportant things.

I was working in a tall building known as the Philosophenturm – the philosophers’ tower, which housed offices for the humanities, and suddenly I heard shouting down in the streets. I looked out, and saw all these young people milling in the streets, protesting the bombing and setting things on fire. I turned the radio on, and there was a CNN reporter in Baghdad. It was horrific – grotesque – what was happening: all-out war in Baghdad and in the streets below me. And here I was, trapped in the proverbial ivory tower, completely detached from anything of substance, poring over old Greek manuscripts. If I could put my finger on one place in my life where I almost snapped, it was there.

The second decisive event came the following week, when a couple – good friends of ours who had been married for ten years – told us that they were separating. Ulrike and I both felt then, and in the weeks and months afterwards, that we were actually on the same path: that there was nothing holding our marriage together that hadn’t also been holding our friends’ marriage together, so to speak. It left us wondering how we could change our life.

Then the Comers heard about Michaelshof, a Bruderhof community in Germany, and out of curiosity made plans to visit.

All we really knew was that we didn’t want to slide into a life of materialism: we had just bought a new stereo system, and were talking about getting a car. And we knew that we wanted to be part of a church where we could do things together, also as a family.

We felt that the “modern” way of life, where each spouse is focused on working to pay the bills while the children are off on their own all day in school, was ultimately destructive. It pulls you in all directions at once. It never comes together anywhere. It never allows you to commit to anything, or even to really contribute to something bigger than your own happiness.

When we drove into the driveway, we knew we were home. We asked to become members the same week. Later, people wondered what had made us decide so fast. But there was really no decision to make. When you’re drowning and somebody throws you a life ring, you just grab it.

In retrospect, Kim says he feels it was “a grace” that they weren’t looking for community per se: “We knew people who went from one community to another, shopping for the ideal place. We were spared all that.”

At the Bruderhof, he found a new context for addressing old challenges:

My whole life has been blessed (or plagued, according to my mood!) by different forms of community, so I have hardly ever experienced loneliness in the sense of social isolation. But I would say that none of them, including marriage and Bruderhof life, have solved or resolved or eliminated my tendency toward being a loner, or feeling alone. In some ways,

I would even say that the aspiration to community exposes and highlights the problem.

But working through his problems with others who have made an unconditional voluntary commitment to each other provides “a security which stands in stark contrast to the precariousness of other human relationships.” True community “does not depend on living up to a particular standard,” but “requires honesty, forgiveness, and vulnerability. You can live alongside others without those, and it may look and feel like community, but without them, you are missing its essence.”

This vulnerability begins in one’s relationship with God. Kim explains:

It is before God himself that you have to own up to your own weaknesses, and to the patent discrepancies between the person that you would like to be (that is, the person you would like others to see) and the person that you actually are. Someone once said that God doesn’t love the imaginary person you try to be; he can only love you as you really are.

That was my struggle as a young man. I was angry about who I had found out I really was. Once you can accept who you are, and accept God’s love for you, the community you have with him will allow you to overcome your lack of confidence, and your isolation, and to find community with others.

2 minute read

Read More15 minute read

Read More7 minute read

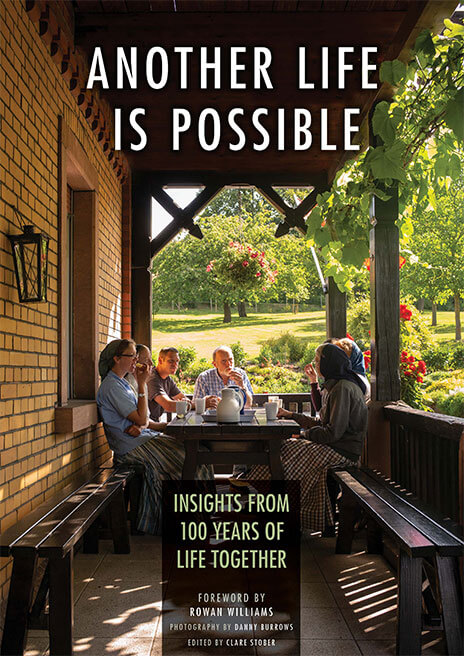

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.