Advice from a single mom dying of cancer

Adima Shirky (1994 –)

3 minute read

Read MoreElse has worked with children and teens in London, Manhattan, South Africa, Nigeria, and Northern Ireland, as well as in Bruderhof schools in rural England, Pennsylvania, and upstate New York. Since 2007, she has taught at Keilhau, a progressive independent school in Germany.

Her interest was kindled at the age of eight, when a teacher showed her class photographs of starving Sudanese children:

Sudan was in the middle of a civil war, and there was no way of getting food convoys to these children. They had distended bellies because of malnutrition. I remember sitting there as a child and saying, “I’m going to do something about this.” Those pictures made me determined to help other children, come what may: to save children dying because of injustice, greed, or war, or simply because no one loved them. As I grew older, I knew I wanted to follow Jesus, and that had to mean giving water to the thirsty and food to the hungry.

I finished high school a year early, landed a place at the university where I planned to study teaching, informed them that I was taking a gap year, and flew to South Africa to help in a kindergarten run by an acquaintance of my father’s. I worked in an impoverished black township in the Kalahari Desert for the next nine months, caring for street urchins whose parents were at work all day – children as young as one and a half.

I remember visiting the family of one of the children we had in the kindergarten and they slaughtered the only hen for me. I felt terrible. I wanted to feed them, and they were feeding me. But I had to accept it because it was done with such love. I didn’t need a chicken. It was almost a slap in my face: “Am I the answer to the need of the world? Who actually is putting food on the table?”

After violence erupted in South Africa I found myself in Nigeria, where the Bruderhof had a presence for some years. This time, money was available to feed and to give clothes to the children. But I never had the feeling that I was doing more than running crazily around trying to fill bowls that were always empty and give what was never, ever, enough – because, the fact is, we all are greedy and we actually all want more than our share. In a way, that bashed my trust in human nature. I left Nigeria discouraged, disheartened, and disillusioned, and wondering about who the poor really were.

Else returned to England and from 1992 to 1996 studied teaching at London’s Roehampton Institute. During rotations at schools in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, she found her idealism bumping against circumstances she couldn’t escape or change. Despite her best efforts, she often saw only limited success, or none at all.

I always looked for schools on the Ministry of Education’s “red list” – schools the government had condemned, pending a deadline for improvement – and chose them: I worked in Brixton, which was known for the Mafia’s presence there, and Southwark and Bermondsey, which had huge numbers of desperately poor migrant families. Those children were trapped between terrible histories and bleak futures; they were doomed to fail before they ever started school. I was determined to do whatever I could to improve their lives.

In Brixton, Else was assigned a class of thirty-three children, all from troubled backgrounds.

One of them was a Sudanese boy whose mother had been killed in the civil war, and whose father had fled with him to London and remarried. This little boy’s stepmother hated him, and locked him in his room every afternoon when he got home. He was being fed through the cat flap. The poor child was unkempt, and he smelled. To me, it was clear: he was the child I had dedicated my life to when I was eight.

And yet, Else was unable to save him. On the contrary, she was eventually forced to report him to the authorities after a violent incident in which he tried to stab a classmate with a knife – and ended up cutting her when she intervened.

That was the beginning, the very, very beginning of a long, long walk. I returned to the Bruderhof. I had to do something for the entire world, and this was the only way I could do it.

When children carry a wound openly, you can help them and interact with them, and very often, their peers will too. I’m always amazed by the community I sense here among children who are openly broken.

I loved my work in the Bruderhof schools. I felt I was doing something. It fulfilled the need in me to feel like I was doing something for children, for the future, for building up something positive that would help society at large.

However, Else’s road continued to be rocky. “I was a popular, capable teacher with big classes,” she says. “What was missing was the knowledge which I’d once had, and which I’d lost, that it’s not me who saves the world, it’s Jesus.”

She took a sabbatical, working with migrants in Syracuse, New York, and digging deep in the Bible in her search for answers.

The first thing I did was to get a brand new Bible. I said, “I’m starting new. I’m starting my search from zero now.” I went to my bedroom and started reading it from page zero on. Of course when you read straight through the Old Testament, you’re like, “Gosh, is there enlightenment here?” It can be pretty hefty.

Then at one point it came to me that every few pages I was hearing the same message over, and over, and over again, and that message was, “And then they shall know that I am their Lord and God.” Suddenly the whole Old Testament took on a whole new meaning. The whole New Testament took on a whole new meaning: “And then they shall know that I am their Lord, their God.” That was spoken to the whole earth, to all the poorest, to all the hungriest, to all the thirstiest, to all the neediest, to those who could get their act right, to those who couldn’t get their act right. That was all that God wanted, that we would know that he was our Lord and God.

It suddenly struck me that for all these years I’d run. I’d run from truly giving everything to God because I’d been proud, because I wanted to run my own thing, because I hadn’t recognized God as Lord. I had been recognizing Else Arnold as some kind of saving force, over and over again.

Since 2007, the Bruderhof has asked Else to work at Keilhau in Germany, the school previously owned by Annemarie Wächter Arnold’s family.

Keilhau is a 200-year-old integrated boarding and day school for students from the first through the tenth grades begun by Friedrich Froebel, the founder of the kindergarten movement. Else notes that his ideas about teaching form the cornerstone of Bruderhof education too:

Froebel believed that the purpose of education was all about the development of the whole child, to bring a child to unity with nature, unity with himself, unity with his fellow man and unity with God. He felt that the best setting in which to raise a child was a cohesive, communal one – a school where teachers work together in relation to the children in their care. One of his mottos was “Live for the children!”

In practical terms, Keilhau – much like a Bruderhof school – has an afternoon program, which includes everything from camp crafts to activities like trail maintenance in the woods surrounding the school, swimming in the school pond, learning to repair bicycles, and going on cycling excursions. In the younger grades, students are also given time each day for free, unstructured play.

If you send your child here, you’re not doing it because you hope to ensure a place for them at some elite university. On the contrary, you’re voting against that sort of education. You’re making a decision in defense of childhood.

Reverence for childhood is at the heart of Froebel’s approach to education. He compared children to flowers. Every flower has the same basic needs: soil to grow in, and sun and rain. But beyond that, there are differences that must be taken into account, if each one is to thrive and bloom. What kind of soil? How much sun, or rain?

Speaking of Froebel’s image of children as flowers, one of his last instructions, as he lay dying, was, “Look after my weeds, too.” Keilhau does have weeds. As an integrated school, it has children of all backgrounds and abilities (or disabilities!), including high-achieving students from “good” homes and children from thoroughly dysfunctional situations who have suffered severe neglect and abuse. We have the whole range.

But if you take his instruction about “weeds” in the context of the theories and methods he dedicated his life to, it’s obvious that he doesn’t actually consider them as such. He called them that to draw attention to their hidden beauty – to help us see that a stray plant can have a precious flower too.

Else often wonders how children who spend much of their childhood between appointments with mental health professionals, social workers, and family counsellors can be expected to focus on academic work, let alone excel at it.

I often feel quite helpless when facing such children in my classroom. They’re known as verhaltensauffällige Kinder in Germany – literally, kids whose behavior makes them noticeable, in a negative way, of course. All too often, they’ve been treated, for as long as they can remember, as a problem, a quandary, a source of frustration.

Given what some of them have experienced, it’s hardly surprising. You can’t easily heal the injuries that have been done to their souls. And yet, sometimes it is the most deeply wounded ones who are the most loving and grateful and, in a way, the most childlike. Maybe it’s because they’re so hungry for something else.

When children carry a wound openly, you can help them and interact with them, and very often, their peers will too. I’m always amazed by the community I sense here among children who are openly broken. They might not always get along, but they understand each other deeply and look out for one another.

On the other hand, I have students who are always in line. Good, quiet kids who seem to be doing fine, and might really be. Regardless of where I’ve taught, those are the ones I tend to worry about most. They’re the ones who the other kids can’t relate to. And nor can I, because they never give me a handle – a way to catch their heart. At the end of each school year, at graduation, there’s always a handful of teens where I have to say, “There’s a student I never reached.” I may have said “Good morning” a thousand times, but beyond that, I find myself wondering, “Did you ever progress to talking with them about something that really mattered?”

Again, it comes down to love. If you love someone, you allow them to blossom. You unleash a positive force in that person, something that affirms life and then spreads and gives life to others. I think – this is true of me, and probably of most adults – that we’re much too sparing with our love.

3 minute read

Read More13 minute read

Read More7 minute read

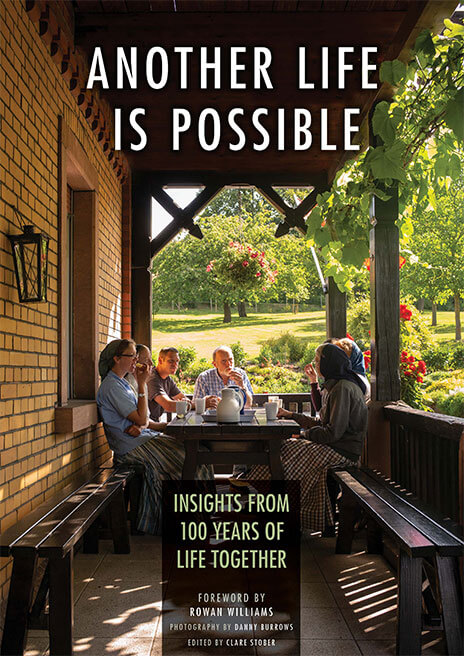

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.