A CEO with a unique set of challenges and opportunities – and no paycheck

John Rhodes (1951 –)

6 minute read

Read MoreTom Potts was born into a prominent Philadelphia Quaker family. He went to Haverford College, where he was a fullback on the soccer team, and then started working at the steel warehousing company his extended family owned. During World War II, the steel industry was regulated in service of the war effort and Tom, who took Quakerism’s traditional pacifism seriously, refused to cooperate. Instead, he went to work for the American Friends Service Committee, and was assigned to manage Civilian Public Service camps during the war as an alternative to military service. Florrie, whom he had met and married in 1934, came with him.

After the war, Tom and Florrie resumed their life in Philadelphia: Sunday gatherings at the Friends Meeting and private schools for their three children. As Florrie later described, “we were on a lot of committees and working with good causes, race relations and sharecroppers. But nothing specially came of it.” Through their Quaker connections, they met and eventually hosted members of the Bruderhof who were travelling in the United States fundraising for the hospital in Paraguay. Tom and Florrie’s decision to travel there and then to become members of the Bruderhof is best explained by Tom in an open letter that he sent to the Friends Meeting in 1952:

For all my adult life I have been frustrated by the contradiction between ordinary American life and the impossible teaching of Jesus’ second commandment, “Love thy neighbor as thyself.” I make out all right during the week: I have a good job and I am part owner of a steel warehouse. We have a most congenial working group and enjoy the game of competing in the marketplace for the available business. We advertise honestly, we charge fair prices, we are concerned about good employee relations, we have a Christmas party, we give generously to the community chest, and we have a profit-sharing scheme. But do I love my neighbor as myself? Am I concerned for the clerk who has come to work in the streetcar while I drive a big car? Do I give the community chest just what I don’t need anyway? Do I share the profit in reality, or do I save a big percentage for my old age, before the distribution? Yet, if I gave it all away, what would my family and I live on? How foolish can you get?

But Jesus did not say, “Love your neighbor after taking care of yourself.” Then on Sunday when I go to meeting for worship of the Society of Friends I realize again and again that all men are children of God and brothers to each other. But what do I do about it? Periodically Friends ask themselves searching queries such as: “Do you keep to simplicity and moderation in your manner of living, in your pursuit of business?” We have two cars. We send our children to private schools and buy them all the clothes and incidentals they want for keeping up with the Joneses. We get for ourselves pretty much what we want. Is that simplicity? How about the business? To what purpose would I spend my major time and energy for the next (and last) twenty years in building our business to two, three, ten times its present size? I would double my income, triple my worries, and perhaps donate more to good causes. But would the donations of money, however large, serve to bring the kingdom here on earth, as would the widow’s mite of my waning energies devoted to a Christian system?

America is rapidly being taken over by the military. I pay a healthy income tax, far more than I am able to give to the Friends Peace Committee. Yet another query says: “Do you faithfully maintain our testimony against preparation for war as inconsistent with the spirit and teachings of Christ?”

Our social and economic system is based on the premise that if each looks out for himself the end result will benefit everyone. But does it? What about the third of our nation who are still ill fed, ill housed, and ill clothed, not to speak of the millions upon millions in the underdeveloped parts of the world? The query says, “What are you doing to create a social and economic system which will so function as to sustain and enrich life for all?”

Each person surrenders his will, his talents, his possessions to God, and together they seek a life of true unity based on love for all. Unbelieving, I took my wife and three children 10,000 miles to see if it could be true. And it was.

The contradiction is everywhere apparent. In order not to feel completely frustrated during these times of soul-searching, I have long reasoned that Jesus must have been setting up an ideal towards which mankind should work and might attain in a few thousand years. And then we discovered the Society of Brothers [as the Bruderhof was known at the time]. They said they were trying to live by the Sermon on the Mount. Traveling brothers told us of the communities in Paraguay, Uruguay, and England, where more than 850 people are living a life of complete sharing. Each person surrenders his will, his talents, his possessions to God, and together they seek a life of true unity based on love for all.

Unbelieving, I took my wife and three children 10,000 miles to see if it could be true. And it was. Their social and economic system is based on the premise that if each one, having faith in God, looks out for his brother, the end result will benefit all, including himself. Men and women from eighteen countries, formerly from all walks of life and all rungs of the social ladder, are living together as brothers and sisters, helping one another, working hard, and experiencing deep spiritual joy. How can I do anything else but settle my affairs and join the work of spreading the news that it is possible to live in accord with the spiritual laws of the universe here and now?

My contribution will be small. But however small, I shall be advancing a practical way of living which does, in actuality and in the words of the query, accept all without discrimination because of race, creed, or social class, and where all are treated as brothers and equals.

You could say I am assembling this part, but what I am really doing is thinking about the child that will use it one day.

And so Tom and Florrie’s life in community began. When Woodcrest, the first American location, was founded in 1954, the Potts family moved there and Tom was asked to manage the community’s woodworking business. Florrie was his secretary, working at a desk facing his and helping to organize the sales staff. At that time Community Playthings’ product line consisted of wooden building blocks and a limited selection of classroom furnishings which were marketed to schools and nurseries. The manufacturing facility was primitive and the community was in debt. Under Tom’s leadership over the next four decades, Community Playthings became a well-regarded, internationally distributed company selling wooden toys, play equipment, and classroom furniture. In the late 1970s, when children with disabilities began to be integrated into classrooms, teachers from a school near one of the Community Playthings workshops requested chairs modified for these new students. Under Tom’s leadership this opening developed into a new business, Rifton Equipment, which now matches Community Playthings in size.

Together, the businesses provided not only income to support the communities in the United States and England, but meaningful work for its members. The core purpose of the community was always more important to Tom than profit: if sales were high and the overtime required to make the products started interfering with community life, Tom would quietly put some orders in a desk drawer to wait for calmer times. He always took care that the operation of the businesses reflected the community’s values: that customers and vendors were treated with respect and that the design and manufacture of the products reflected love for the children who would use them. (Tom’s three business principles were quality, quality, and quality.) He felt accountable to the community membership for his business decisions, once apologizing in tears during a church meeting for spending money on a new marketing approach that had failed to pay off.

Tom was a humble man who never took himself too seriously. Hearing himself described as an expert he once said, “Oh, you know what an expert is. An ex is a has-been, and a spurt is just a drip under pressure.” Known to the children of the community as “Wolfie,” he would interrupt a business call or meeting to growl theatrically if a child looked in the door of his office (as they were welcome to do, knowing that there was candy hidden in the desk).

And then, after four decades of managing a successful business, Tom handed over responsibility for it to a younger brother, John Rhodes, who had been learning from him for some years. (Read John’s story here.) Too old to lead a business, but still full of life, Tom went to work in the Rifton Equipment shop, threading straps on the sandals of mobility equipment. A visitor to the shop once asked him about his work. “You could say I am assembling this part,” Tom said, “but what I am really doing is thinking about the child that will use it one day.”

Tom and Florrie never lost some aspects of their Quaker upbringing. Evening gatherings at their home ended at 10:00, “Quaker midnight.” Quakers are “plain people” and the Pottses loved simplicity: anyone was welcome at their table at noon on Sunday (and many came) when they served “Sunday soup” made from leftover vegetables from the community kitchen. And they addressed each other in the Quaker manner as “thee” and “thou” with the great love that defined their relationship. “Now here comes Florrie,” Tom would say as his wife of sixty-four years approached. “Doesn’t she look lovely?”

6 minute read

Read More3 minute read

Read More15 minute read

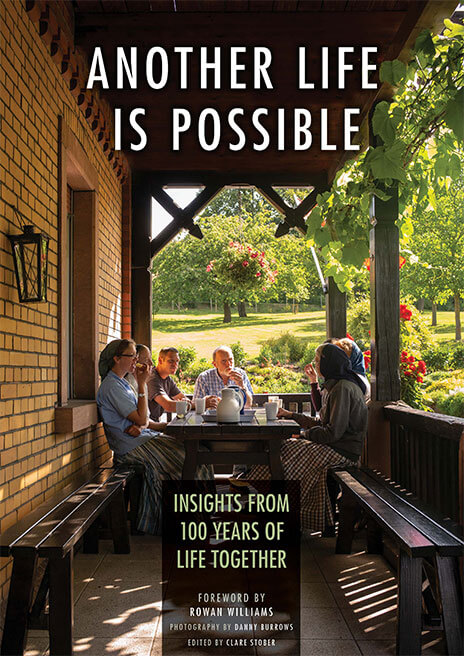

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.