Readiness to work wherever needed makes community life possible

Jeremy Decker (1986 –)

1 minute read

Read MoreFor the last three decades, John has run the Bruderhof’s businesses, Community Playthings and Rifton Equipment. He has given considerable thought to the place of technology in community, and in 2017 he summarized some of those thoughts in an essay for Plough Quarterly:

Founded in 1948 by communitarian pacifists in Georgia, since the 1950s Community Playthings has been the main source of income and work for the members of the Bruderhof. . . . All those who work in the company are my fellow Bruderhof members; in keeping with our vow of personal poverty, none of us owns a share or earns a paycheck, with all earnings going to support the community or to fund its philanthropic and missionary projects.

Despite its communal context, Community Playthings has thrived in the capitalist marketplace. Along with Rifton Equipment, another community-run company that makes therapeutic equipment for people with disabilities, it sells to customers around the world; in 1998, earnings were covering all costs for two thousand people in eight Bruderhof locations in the United States and Europe. Both companies, though medium-sized in terms of market share, are recognized as industry leaders for their durable products and vanguard designs. Such success sprang at least in part from our adoption of innovative technologies. The company had computerized already in 1979, buying a Wang minicomputer; a decade later, a second growth spurt resulted from adopting the Japanese “Just-in-Time” manufacturing philosophy, which made extensive use of manufacturing data.

Any use of technology that undermines the richness of human relationships must be presumed suspect, especially if it encourages passivity rather than creativity. That’s why we minimize the use of social media in our communities.

Until the 1990s, bringing new technologies into the business was rarely controversial. Then, in the 1990s, the company introduced email. At first, everyone was smitten, but eventually there was a backlash, as frustration with the unintended consequences of electronic communication mounted. Before long, there were proposals for an enterprise-wide email ban.

At the time, I argued that in our communication-rich environment – we live and work together, meet daily for communal meals and worship, and are committed to avoiding gossip and backbiting – email’s weaknesses should be manageable. But it didn’t play out that way. And interpersonal relationships suffered as a result.

Now, email seems outdated (we still use it – our self-imposed ban only lasted a few weeks). But look at the role social media plays today – at Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat. These things have completely altered the way people relate. In many cases, they represent a huge, unmanageable entity that has taken over their lives.

Paraphrasing French thinker Jacques Ellul, John says that the outcome of a given form of technology depends less on the user’s intent than on the structure of that technology.

Programming our company’s first computer, I realized how quickly I became obsessive about the project. In terms of its usefulness to the business, there’s no question how valuable it was. But what it did to my mind is another question entirely. I found myself thinking all day long about how to fix this algorithm, how to make this next thing happen. And it became a very lopsided activity. So you need to keep your eyes open. It is vital to remain technology’s master, and not become its slave.

What this demands of us is not outright rejection or acceptance, but constant careful thought about technology’s consequences: Any use of technology that undermines the richness of human relationships must be presumed suspect, especially if it encourages passivity rather than creativity. That’s why we minimize the use of social media in our communities, and why our homes don’t have television. And why our laptops stay in the office when five o’clock rolls around. If a form of technology is proving deleterious to your relationships with others, you have to have the guts to drop it. Don’t be afraid to walk away.

Ultimately, John points out that when the technology at hand “enables people to work with all the faculties of their being, and to work well with one another,” it has “found its rightful place.”

We intentionally hang on to work that could easily be outsourced, or entirely replaced with an automated piece of machinery. Because when a brother or sister who is, let’s say, seventy-five years old, comes down to our shop and wants to put in a few hours of meaningful work – not busywork – we want to have it available for them. We will accept a certain level of inefficiency just to make that possible.

1 minute read

Read More2 minute read

Read More2 minute read

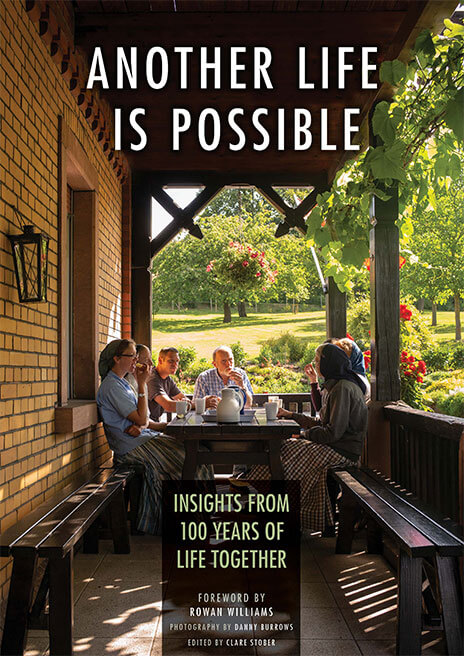

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.