A gardener with a passion for sustainable agriculture

Jeffrey King (1987 –)

2 minute read

Read MoreThe first half of the twentieth century was full of new technological marvels and horrors. In 1945, the United States dropped atomic bombs on two Japanese cities, finally ending World War II but also showing, in stark destruction and staggering loss of life, the power of scientific advances.

On a Paraguayan Bruderhof settlement far from Japan, Philip Britts, a British scientist, poet, and essayist, wrote:

Are we really standing at the beginning of a new age of scientific development, of supersonic speeds, of atomic energy, of more and more wonderful machines? . . . Are we really about to enter an era of greater wealth, greater luxury, greater leisure, and emancipation from drudgery? Or has this age reached its climax, and will this civilization destroy itself with those forces which it has created?

Time alone will answer this question, but it is by no means certain that the scales will tip for peace and plenty. To sail onwards in the arrogant confidence that man can manipulate these tremendous forces for the good of all, is to drift toward catastrophe. Is not this the poison of the age, the belief of man in man?

For Philip, the news from Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a dreadful confirmation of the things he had worried about all along, that humans would seize more power, especially through technological innovation, than they could responsibly wield.

Philip was raised in the busy port city of Bristol, and attended the university there. Upon graduating and being named a Fellow of England’s Royal Horticultural Society, he married a childhood friend, Joan Grayling, and bought a comfortable stone house with a walled garden.

Then war broke out. A convinced pacifist, Philip had founded a local chapter of the Peace Pledge Union, a national pacifist organization. After England entered the war in September 1939, however, the movement quickly caved in. Thousands of PPU members broke their pledge and threw their energies into defending the country against the threat of an invasion by Hitler.

Just at this juncture, feeling isolated in their convictions, Philip and Joan heard of the Bruderhof. Intrigued by its consistent stand for peace and the witness of its classless, international membership, they cycled there with their dog – a thirty-mile trip. After a week’s visit, they decided to join.

That Christmas, Philip wrote a poem that expresses the heart of his calling:

The Carol of the Seekers

We have not come like Eastern kings

With gifts upon the pommel lying.

Our hands are empty, and we came

Because we heard a baby crying.

We have not come like questing knights

With fiery swords and banners flying.

We heard a call and hurried here –

The call was like a baby crying.

But we have come with open hearts

From places where the torch is dying.

We seek a manger and a cross

Because we heard a baby crying.

Already before the young couple came to stay in November, German members of the community were being called to appear before local tribunals to determine if, as “enemy aliens,” they should be interned. Finally, the community was issued an ultimatum: it would either assent to having its German members interned for the duration of the war, or all its members would have to leave together. Taking the latter option, the community decided to look for a new home overseas, and found that the only country that would accept such a motley collection of nationals was Paraguay. By the end of 1941, everyone had miraculously made it across the submarine-infested Atlantic and resettled in South America.

In Paraguay, Philip’s agricultural training was vital to the community’s survival. It took time to build up a garden large enough to feed three hundred and fifty people, but under the expert eye of Philip and other members, the first crops – beans, corn, manioc, rice, and sweet potatoes – were soon being harvested. Meanwhile, he experimented with plots of wheat, pineapple, grapefruit, and bananas, and took copious notes. Alongside his careful observations were notes and poems that expressed his sense of wonder at the beauty of creation:

The Field and the Moment

The shadows of three men sowing watermelons

Grew very long behind them as they crept down the field.

A pair of parrots flying homeward

Shouted noisily to them to look at the sky:

But they continued stooping and dibbling the seed in the earth.

In this way they grew a number more melons

And missed what was written in that particular sunset,

Which had never been written before

And, of course, will never be written again.

In 1943 Philip visited STICA (Servicio Técnico Interamericano de Cooperación Agrícola), a US-funded agricultural institute based in Asunción, to learn what crops might be most suitable for the community’s land. A month later, two of its American researchers returned the visit. They were so impressed by the community’s farming – and by Philip’s record-keeping – that they offered him a job.

Although it meant leaving his young wife and their five-month-old child, Simon, the community needed the money, and Philip agreed to take the job. For most of the next two years, he lived in Asunción. Among his successes was the development of a green bean variety later planted by farmers across the country, and a grass variety that resulted in a better milk yield from dairy herds.

After returning to the Bruderhof, Philip continued his work with the institute. STICA rented twenty acres of Bruderhof land, where Philip set up three experimental farms. His research notes fill eight volumes.

But, even as he worked at the institute, Philip had reservations about developments in agriculture. The Green Revolution started in the 1940s in Mexico, where American scientists developed new varieties of wheat with increased yield and high disease-resistance. These strains were dependent on big machinery, high-volume irrigation, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides. In an unfinished essay, Philip worried that chemical-dependent farming would have devastating long-term results:

Adam was charged with the double task to “subdue and replenish” the earth. If a graph could be plotted of the subjection of nature by man, it would show a line, rising slowly at first, through several thousand years, then abruptly and very steeply in the last few years. A graph of the replenishment of the earth by man would probably show a slow rise throughout the centuries, but instead of following the sharp rise of the line of subjection in modern times, would perhaps curve downwards. This in spite of the extensive use of fertilizers, because chemicals without humus do not give lasting or balanced replenishment.

Where will the lines go from now on? Obviously if the measure of subjection continues to rise, and the measure of replenishment falls, if the lines get farther apart, nature will rebel, and bring down the measure of subjection by such hard steps as erosion, sterility, and disease.

Man’s relationship to the land must be true and just, but it is only possible when his relationship to his fellow man is true and just and organic.

In contrast, his own research focused on organic methods that worked with, rather than against, nature. But on its own, organic farming was not enough:

Man’s relationship to the land must be true and just, but it is only possible when his relationship to his fellow man is true and just and organic. Thus we do try to farm organically, but we see this as only one part of an organic life, existing in the context of a search for truth along the whole line. This gives rise to social justice as brotherhood, to economic justice as community of goods. We see these conditions as the necessary basis for a true attitude towards the land and towards work.

To the question, “How shall we farm?” must be added the question, “How shall we live?”

The only answer, to Philip’s mind, was Christian community.

Instead of the glittering palace of manifold divisions, let us seek a simple house with an open door. Instead of the towering organization of worldly skill and worldly knowledge, let us seek a humble trust in God. Let us make the unconditional surrender to the spirit of love. “Except a man be born again he cannot enter the kingdom of heaven.” Let us beware of trying to save ourselves by going the two ways. “He who seeks his life shall lose it.” Are we standing at the brink of long vistas of prosperous evolution, or is civilization moving towards its own destruction? Has it the seeds of life or death within it?

Our only choice is a choice of service, and service means deed, not word. It is either-or. Serve one or the other. Prune the great tree of division or plant the new tree of brotherhood.

But Philip was also adamant that community “is not a panacea for the problems of life. The struggle is intensified, not lessened. But mutual aid in love gives strength and joy. So let each one who hears this call add his torch to the fire, so that the light of brotherhood may shine clearly and warmly in the chilly darkness of our times.”

In January 1949, at only thirty-one, Philip died of a rare tropical disease. His death shocked the community. Few had realized the gravity of his illness, and suddenly he was gone. He left three young children and Joan, who was carrying their fourth child.

At the time of his death, Philip’s practical and intellectual work was barely begun. Had his short life done anything to combat the evils – war, injustice, scientific hubris, natural destruction – that he so deplored? This poem, written in 1941 and published posthumously in Water at the Roots, seems to anticipate that question:

That My White Lamb

That my white lamb is being carried off

In steel-like talons to the unknown hills

And is a lost speck only, in the sky –

That is not the chief thing;

Or that I did not have the strength or skill

To drive off the attacker, to defeat

Merciless claw and swift unerring beak

Or shattering wing;

But my fist is smashed and bloody

And my arm is a scarlet rag,

Showing I struck at the eagle –

And that is the chief thing.

Read more of Philip Britt's poetry and writings in the book Water at the Roots.

2 minute read

Read More2 minute read

Read More3 minute read

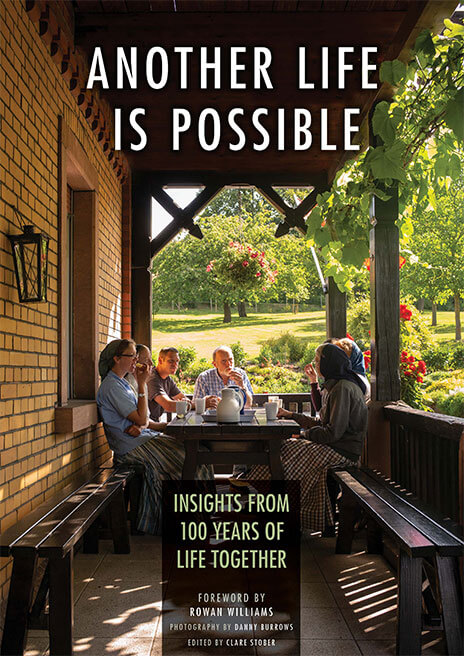

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.