An open door creates community in Durham, North Carolina

Charles Greenyer (1980 –)

2 minute read

Read MoreTo be twenty-one and pregnant wasn’t something Kathy, the daughter of a wealthy Park Avenue dentist, felt ashamed about:

It was my life, and my peers didn’t judge me. A longstanding friendship had dissolved into lust in the backyard of my parents’ suburban Connecticut home on a starry summer night, after a big party and too much drink. Later, the father of my child helped me out of my “difficulty” by driving me down to a New York abortion clinic. He paid half of the cost and we never talked about it again; the whole thing was “simply a procedure,” though to be honest, details like the clear-glass vacuum bottle still haunt me today, half a century later. All I had to say to the one and only friend who challenged the morality of what I had done was a cocky, “God wouldn’t want me to bring a child into this situation.”

And yet, Kathy says, her flippancy masked a deep unease – an unspoken yearning for peace that had accompanied her from childhood, when she sensed a lack of harmony in her own home and among her friends. And her abortion certainly didn’t help matters.

Enrolled at Catholic schools from the first grade through college, she dutifully went to confession, and says that the subsequent feeling of “being right with God was always a source of peace.” On the other hand, she would not have described herself as religious. If anything, she was troubled by the church as an institution. “It seemed so corrupt, and represented so much power and wealth.”

I guess you could say my search was more like a bowlful of discontentment, something that was sort of boiling in me. It’s true that I wanted peace. But how should I even start to look for it? I knew I couldn’t buy it, or barter myself for it. I could see the truth of that all around me – the truth of the Beatles song, “Can’t buy me love.” After all, in Fairfield County, where I lived, there was more than enough opulence. But there was also so much unhappiness, and so many shattered families. Something in me was crying out for something other than that.

Somewhere along the way I heard something that some philosopher said: to find happiness, the individual has to give up himself – to empty and rid himself of everything self-serving and give his heart over to serving others. That really impressed me.

But then came the rebellion of my student years and my anger against the status quo and everything in it that I thought worked against peace and love. I proudly imagined I was making peace: by trying to end the Vietnam War through marching, singing, supporting war resisters, and so on. I thought I could bring some fairness to the plight of the migrant workers by boycotting grapes and causing chaos in the local supermarkets that carried them.

None of it brought me peace because my whole orientation was wrong. Not that I wasn’t serving good causes, but I was my own god: I was the standard by which I judged my life and other people’s lives. I was frightfully, sinfully, willfully my own boss, and I tried to do everything in my own strength. It doesn’t work.

Anyway, by around 1971, I was living in a hippie commune on the land, pooling my money with others, doing yoga, eating brown rice and veggies, and filling whatever void was left with drugs and sex, when a small voice sought me out.

At a book display, I ran into two humble, loving people who radiated a spirit totally new to me. They were from a place called the Bruderhof. “I’d buy one of your books,” I told them, “but I only have a dollar.” That dollar changed my life. The little book I bought with it – a collection of writings by Eberhard Arnold – not only challenged every aspect of my life but also gave me positive answers. Reading it made me realize that everything I was looking for could be found in that radical revolutionary, Jesus Christ. I wasn’t seeking him, but he called me. What’s more, the people who had sold me the book not only believed in its message but were trying to put it into practice. I knew I had to see it for myself.

I was my own god: I was the standard by which I judged my life and other people’s lives. I was frightfully, sinfully, willfully my own boss, and I tried to do everything in my own strength. It doesn’t work.

During her first visit to the community, Kathy still secretly smoked her pot. She told her hosts there were many other ways to find God. They didn’t argue with her, but they didn’t have to. Far more convincing was the atmosphere which enveloped her.

The book I’d bought had talked about the community as an embassy where the laws of the kingdom of God apply, a place where every sin can be confronted and forgiven, and peace reigns. I experienced that as reality. No other place could have fostered the inner change, growth, and healing I so desperately needed. Nowhere else could I have been so clearly and lovingly pointed to the cross, and away from myself and my agony.

And so I joined the Bruderhof. I was relieved to find out that it wasn’t just a holiness trip but a simple, practical life, open to anyone. Undergirding it all was a new (for me) understanding of peace: the peace that points away from the self, and toward community, toward God’s future reign of joy and love. In surrendering and giving myself to that goal, I found what I had always been looking for.

2 minute read

Read More2 minute read

Read More5 minute read

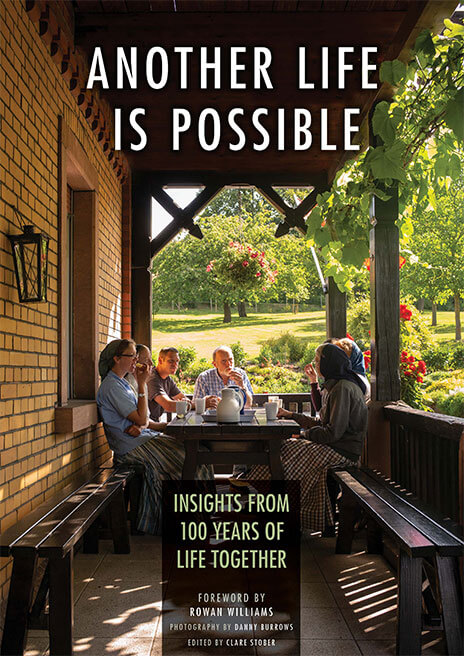

Read MoreWith photography by British photojournalist Danny Burrows, this 300-page hardcover book celebrates what is possible when people take a leap of faith. It will inspire anyone working to build a more just, peaceful, and sustainable future.

Sign-up below to download a free sampler of this book. You'll also be notified by email as new stories are posted.

We will never share your email address with unrelated third parties. Read our Privacy Policy.

Your Turn

Enter your questions or reactions here and we’ll pass it on to author Clare Stober.